As I wrote in October, two spin-off games from the creators of the Yakuza series were recently ported to PC: Judgment and Lost Judgment. I shared my impressions of the first game shortly after it came out. But having played the newer game and taken the time to reflect on it, I’ve decided that Lost Judgment is not only a huge improvement on its predecessor, but it’s also the best Yakuza game in the series.

In addition to having slightly better graphics, Lost Judgment makes smart design decisions that give the game a more enjoyable and cohesive experience than you would expect based on its predecessor. This is in part because of the game’s choice of setting, but also because the developers chose to integrate everything more closely together. That’s what I focus on here.

Back to School

The biggest change in this game is the setting. Like Yakuza: Like a Dragon, Lost Judgment is mostly set mostly in a fictional neighborhood in Yokohama. While the Yokohama map feels less familiar and built out than fictional Tokyo neighborhood the of the mainline Yakuza series, being in a new city gives the game a fresher feel.

This is particular true because of a key addition to the city: a fully-modeled private high school. The main story in Lost Judgment revolves around the main character, Takayuki Yagami, investigating bullying allegations at the high school as well as a murder connected to the school. For this reason, the high school appears in a corner of the map not present in Yakuza: Like a Dragon, and once you enter the high school you will be able to walk through a full-scale Japanese high school, with hallways and corners to navigate. Yagami ends up volunteering as an advisor to an after-school club to further his investigation, which gives him access to the campus and a narrative reason to engage with the students.

This focus on high school has significant implications—and payoffs—for the game. For example, it dramatically elevates the quality of the side quests. As I noted in my review of the original Judgment, while some side quests were fun, many of them were detective missions that repeated the same uninteresting themes like a distrustful boyfriend wanting photographic proof of infidelity. Quality is significantly more even (and high) in Lost Judgment. The school setting allows for consistently varied and engaging sidequests, such as helping middle-aged alumni track down a time capsule of their childhood anxieties and chasing what appears to be a living anatomy mannequin through dimly lit halls at night. Not all sidequests are centered around the school—you’ll still get detective commissions and find distractions on the streets—but the school offers a fresh setting for side stories, resulting in higher quality distractions from the main story.

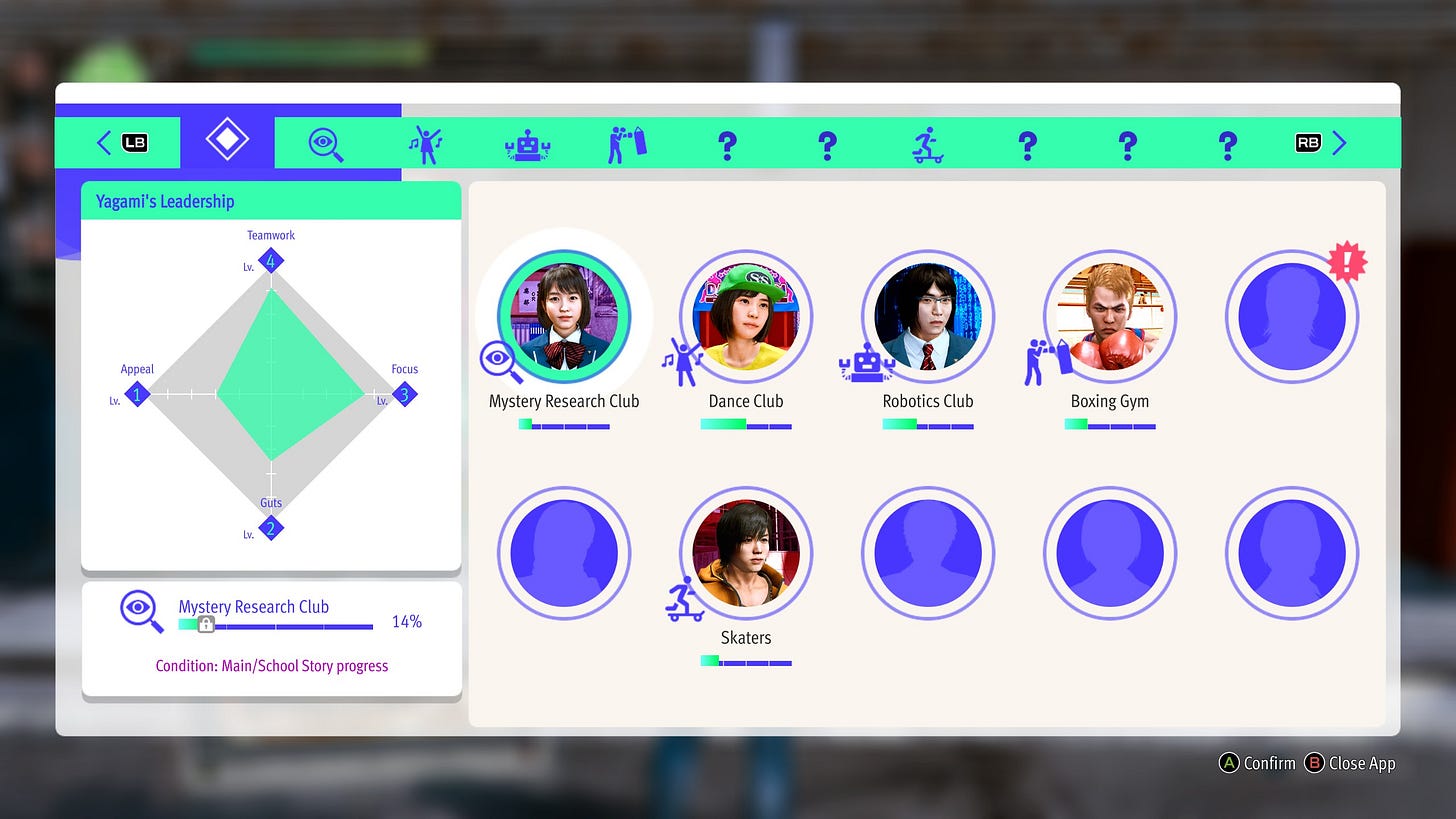

A key piece of this is the School Stories system, which act as fleshed out minigame arcs tied together by an overall story. Past Yakuza games had similarly fleshed out minigames: in Yakuza 5, each of the main characters had a side activity they could do, such as picking up taxi passengers and carefully following traffic laws as they tell you their woes and hunting on a snow-covered mountain, with each excursion limited by the weather and your supplies. Even Yakuza 0 had a long, involved series of toy car races against children needing their dreams crushed.

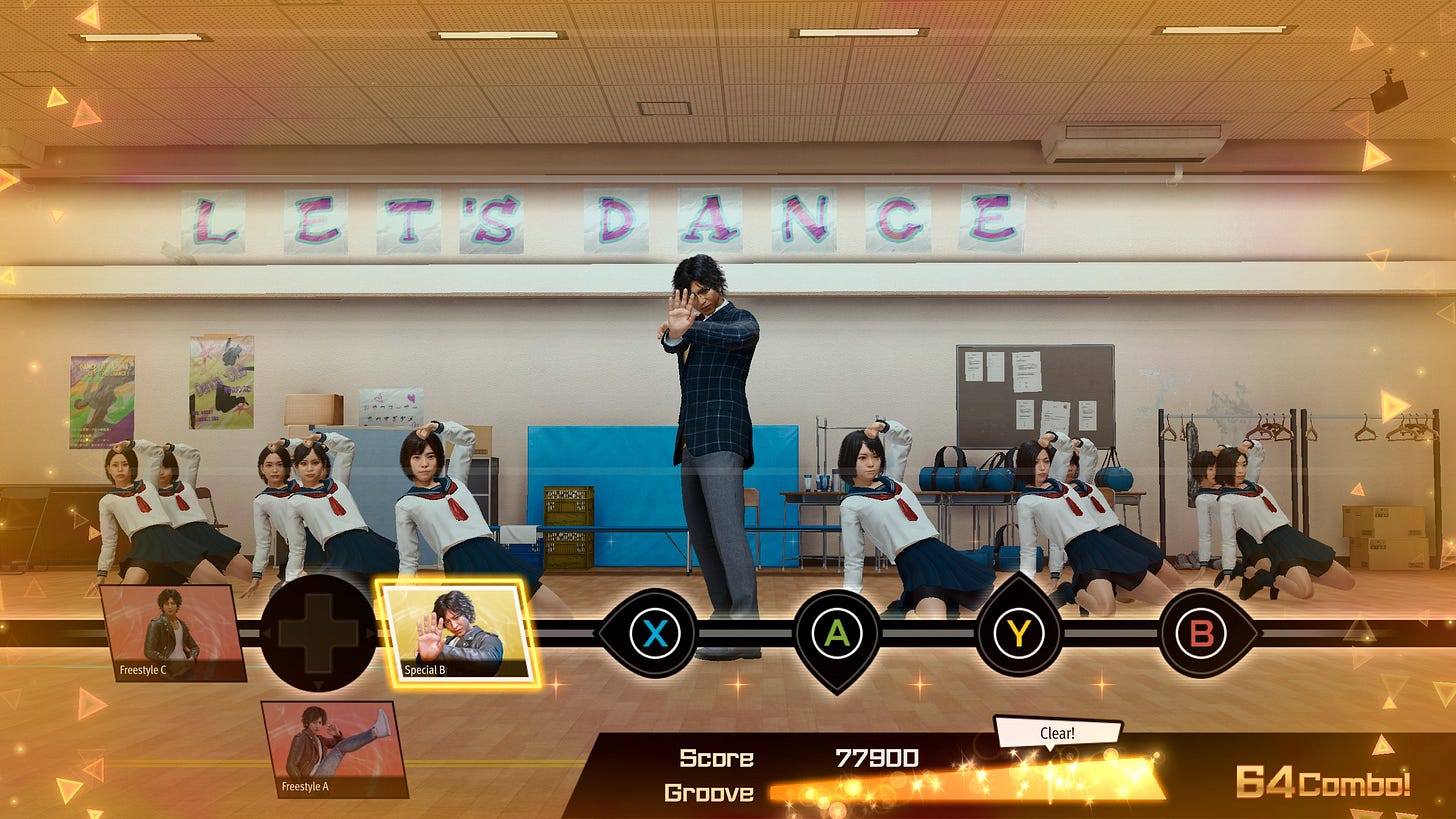

School Stories are Lost Judgment’s version, in which you infiltrate ten school clubs or school-adjacent activities in search of clues about who is causing students to misbehave en masse. Most, though not all, of these clubs have fleshed out storylines as you gain the trust of the members and participate in some sort of activity with the club. For example, advancing the story for the dance club requires playing a rhythm game as the team practices for and competes in several competitions, each using a different song and dance style. The Robotics Club has you scouring the city for components, building robots with those components, and then using the robot to take over territory on a tetris board. And the boxing gym sees you learning to box against former criminals while trying to figure out whether one of them is a vigilante. The mini-games have sufficient variety and depth to feel like their own thing, rather than something intended as a one-off to briefly distract you.

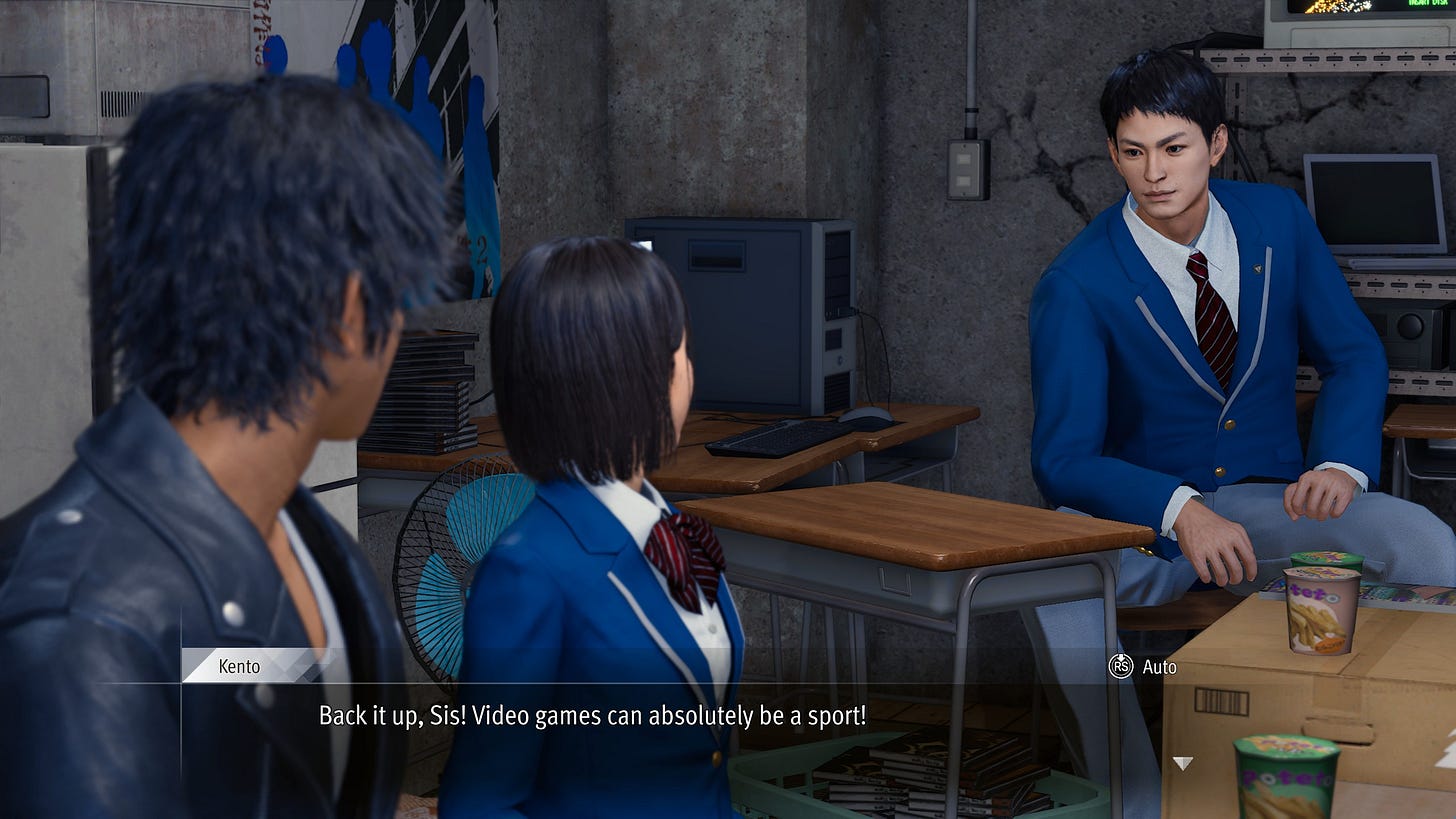

Not all of the clubs in school stories are equally long; one requires winning a few hands of poker, and the “e-sports club” involves a few button-mashing games of Virtua Fighter to expose a cheater. But they have sufficient depth and variety to provide something fresh when you want a break from the main story, and the writing is engaging and endears the characters to you as a player. Plus the music when you are doing tricks at a skate park is catchy.

The school setting also keeps the series fresh through a tonal change from pure crime drama. Typical Yakuza games are very male affairs, with most characters on-screen being men in their 30s or 40s who like to settle problems with their fists. Perhaps this makes sense in the context of gang-centered crime stories, but it gives each game a very similar atmosphere. The centrality of a high school in Lost Judgment means that high schoolers (and their problems) play a prominent point in the game’s narrative, as well as provides more gender balance in the game’s cast. So while you lose a common narrative element in other Yakuza games, you instead get to see how the Yakuza’s teams writers handle the sort of high school coming-of-age themes that might be presented in a Persona game. The Yakuza series has always told versions of “unconfident person figuring themself out in a big city” through adults you meet on the street, but the high school version of that is a bit more mature and a bit more interesting than other depictions within Japanese media. Though you’ll still get to see old and new faces on the street as well.

Unfortunately this also has some downsides. The biggest one is that the game’s main story is much weaker than its predecessor. In the original Judgment, the main story centered around an old murder case that resulted in the protagonist Yagami leaving the legal profession and becoming a private investigator. It worked well as a vehicle to explore Yagami’s backstory (why he became a lawyer, why he choose to leave it after an early success), and it kept players guessing as it drip-fed clues suggesting ties between the old murder cases and more recent cases.

Lost Judgment’s main story is less gripping. The game open with the murder of a young student teacher that becomes a much larger story about high school bullying and how it can drive students to suicide. Aspects of this are interesting in the way that stories re-framing school life can be interesting to anyone who went to a large school, and there are some interesting themes of growing up and the difficulties of high school social life raised by the game.

Unfortunately, the game chooses to continuously escalate the stakes of the plot rather than do something more grounded. As a result, the game eschews a clear antagonist, and instead, by the time the credits role you will have found yourself (1) decrying the murder of a character whose screentime being name-checked as a martyr is greater than their time spent alive, and (2) befriending the person who committed the initial murder that kicked off the whole story. This is a game series with its share of weird plot points, including what remains an incomprehensible reveal in Yakuza 6 about a government official who secretly rebuilt a World War II battleship and was willing to kill anyone who learned of it. But for all the disbelief I suspend for these delightful, ridiculous games, the main story in Lost Judgment tested my limits.

The flaws of the main story are worth it, though. The game has better graphics, side stories, and fighting systems than its predecessor. And the school setting provides a very different setting for the game, making it feel closer to the Yakuza team’s view of Persona than the standard gang drama. As a result, I found myself completing almost everything the game had to offer without meaning to, simply because the distractions were so engaging and fun. This is true whether walking around the city with a crime-fighting shiba or playing a VR board game competing against IP-infringing versions of Yagami’s friends. That is more than I can say for the original Judgment, which wanted you to complete quests for and befriend 50 (fifty!) random people in Tokyo.

If you’ve been interested in the Yakuza series but didn’t want to trudge through 6+ games recounting the story of Kazama Kiryu (and friends), the Judgment series is much more discrete and digestible. And of the two games, Lost Judgment is the stronger.

The Kaito Files

Lost Judgment also includes a separate expansion called The Kaito Files, in which you play as Yagami’s friend and detective partner Kaito, a former yakuza who provides physical backup for Yagami. While Yagami is out of town, Kaito is hired to locate a woman he had almost married before his life of crime and revenge made them separate. Shortly after, he is found by the woman’s delinquent teenage son, who is convinced that Kaito is his father and can help find her. For about 6-10 hours, Kaito will try to locate his old flame while figuring out the truth behind her disappearance and stopping her dumb 14 year-old son from picking fights on the streets of Tokyo.

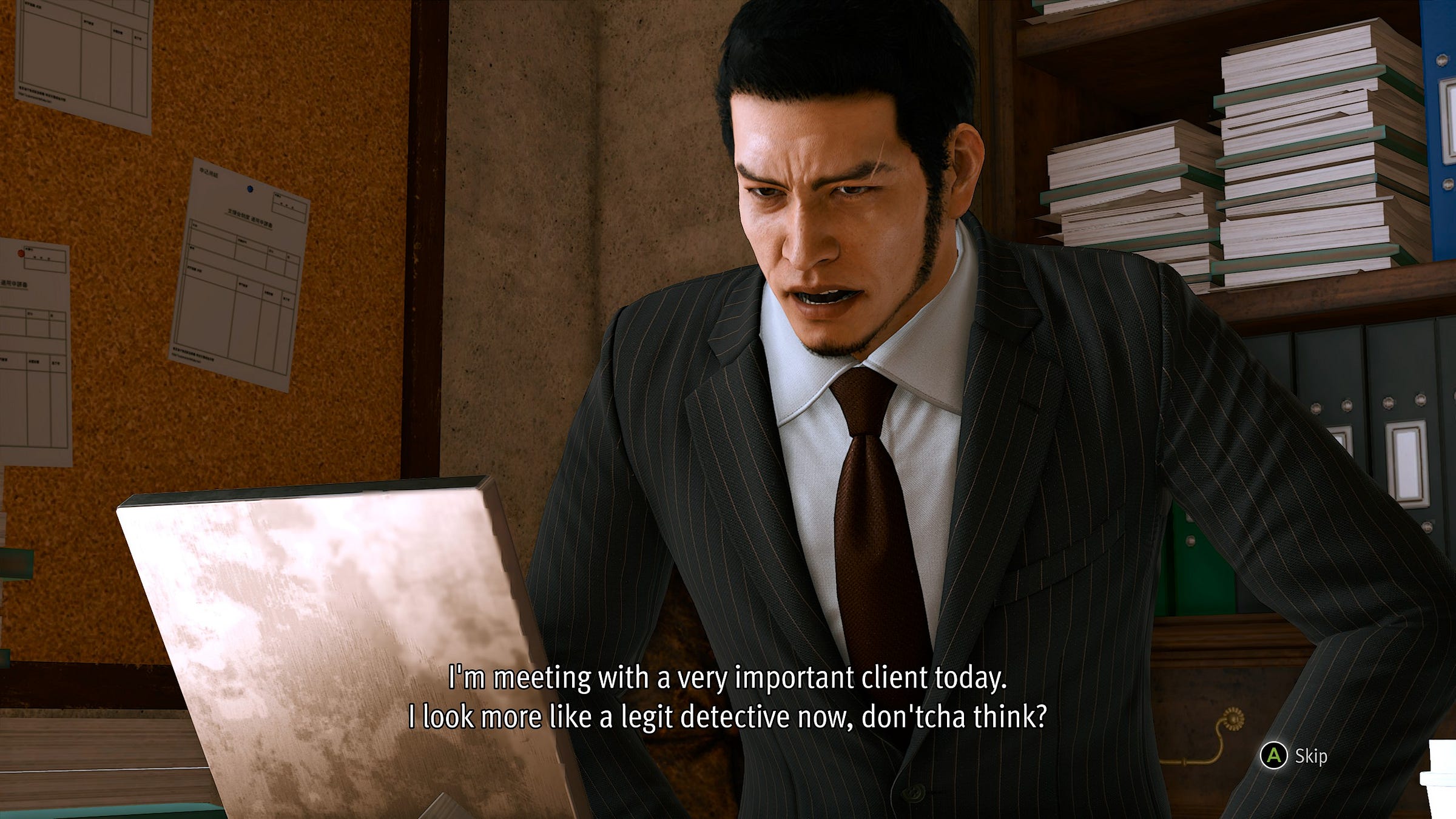

The Kaito Files does exactly what a good expansion should: it offers additional gameplay in a world you enjoy, but with a few twists to make the experience distinct and fresh. Many of the changes in the expansion are a result of Kaito being the playable character. He is more of a brawler than a nimble fighter, so his movements in combat are slower and more powerful. Moreover, while Yagami finds clues by carefully observing a scene and identifying what does not logically belong, Kaito finds clues by using his senses; identifying unusual smells or sounds that others might not be able to pick up.

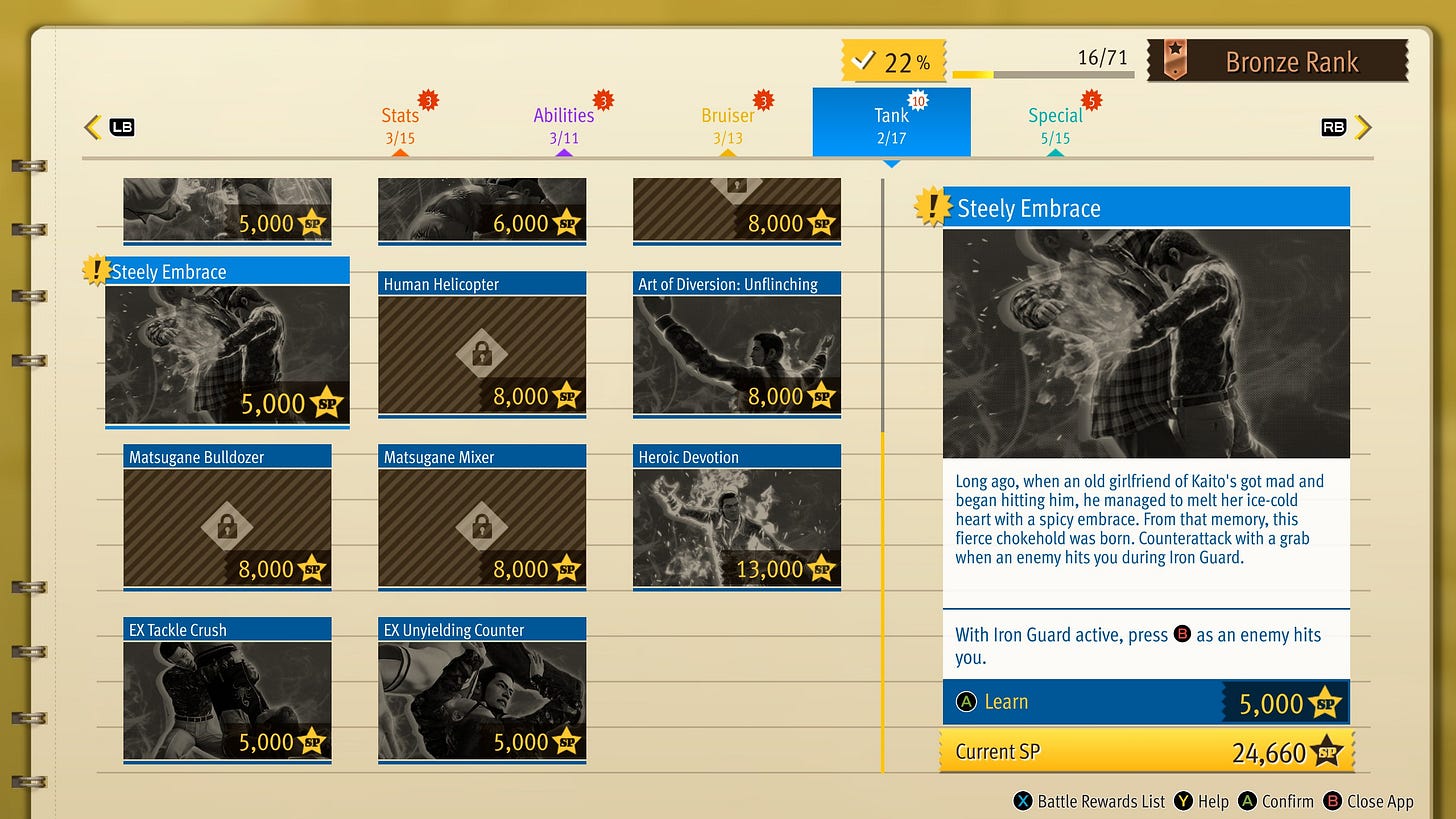

The expansion has other changes to reflect the smaller scope. Instead of grinding experience or playing sidequests to learn special fighting moves, Kaito can instead find glittering representations of his memories when walking around town, where he recalls moments of his gangster past and then gains a new move that corresponds with that memory. It’s a little silly, but it rewards the player for walking around and inhabiting fictional Tokyo as a different character with different experiences, and it lets you quickly pick up new moves if you are observant (or using a guide). And while the expansion doesn’t have sidequests, there are a few activities like finding stray cats that you can do while running around town.

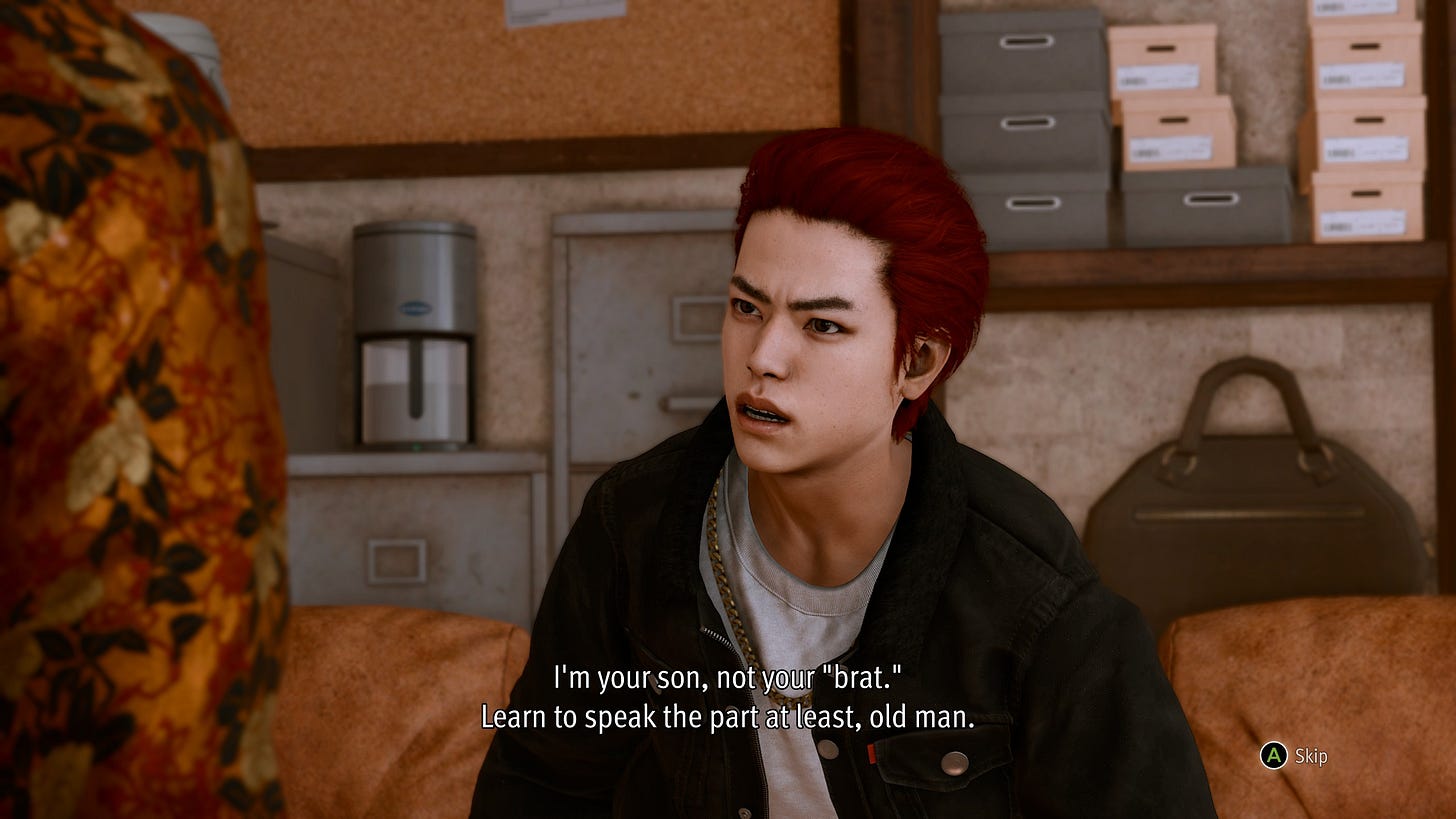

Finally, the expansion’s story is a high point: easily exceeding Lost Judgment’s main story while offering complementary themes that elevate the game as a whole. You will spend most of the game accompanied by Jun, the son of Kaito’s ex who is convinced that Kaito, a cool former gangster, is his father—not the business executive married to his mother who hired Kaito to find her. Jun follows Kaito around, constantly calling him “dad,” and constantly getting into trouble because he thinks he is equally tough to actual gangsters trying to kidnap him. The dynamic between Kaito and Jun quickly endears the child to you, while a little sad about how life shaped him into needing to act tougher than he is. And it shows another side of Kaito, who is sometimes treated as the brute muscle behind a detective agency opened by a disillusioned lawyer. In the Kaito Files, he gets additional complexity, backstory, and the chance to act as a father figure to a teen headed down a similar path.

This fatherly dynamic complements the main story of Lost Judgment and the Yakuza series more broadly. In Lost Judgment, Yagami meets numerous high school students who chafe against their environment and the expectations of adults, finding it easier to act out. In the Kaito Files, you spend the game looking after a young kid who seems headed down the same path, one that leads to a destination you see in the main game. But in the expansion, you get additional insights into how one particular child became a delinquent, and you have more personal investment in his growth due to a shared history with his mother and the boy’s insistence that you, a barely-employable former criminal, are his actual father.

This echoes themes from past Yakuza games, which involve series protagonist Kiryu serving as the adoptive father of Haruka, a young girl whose mother was childhood friends with Kiryu but dies in the first Yakuza game. Because Haruka’s mom died when she was 9, her narrative role in early games is largely as a young child who needs to be looked after and protected. From a gameplay perspective, her main involvement is walking around Tokyo with Kiryu, holding your hand and asking to go into various shops. I found those game segments frustrating.

Haruka’s narrative portrayal suffers because (A) the Yakuza series is not great with female characters in general, (B), in most games she is a pre-teen with minimal agency, and (C) Haruka never shows frustration or negativity. Haruka is largely a plot device in the Yakuza series, either as the little girl forced to run an orphanage Kiryu started out of guilt for his criminal past or as a teen mom whose baby could be the heir to a mafia group. Her bigger role in the series is to characterize Kiryu, who is constantly unsure what to do with Haruka. Kiryu has no idea how to raise a child; he grew up in an orphanage, spent a significant part of his young adulthood in jail for a crime he didn’t commit, and then is forced to take care of an 9 year-old with no other family. He fumbles through it while feeling guilt for the fact that he cannot fully commit to that responsibility.

The Kaito Files act as a foil here, with the young “son” character being old enough to follow you around town and get into fights with you, and with him having (or being given by the writers) the maturity and agency to act as an important part of the narrative. Like Kiryu, Kaito is a former gangster who does not know how to handle a young child looking up to him. But unlike Haruka, Jun idolizes Kaito as the cool father he wants, rather than than the aloof father he has, and Kaito more clearly understand of the future ahead of Jun, since he too joined a yakuza family because he was a teen delinquent with no other family. Because the Yakuza series has explored teen delinquency and the difficulty of yakuza members living “normal” lives such as parenthood, the interactions between Kaito and Jun play off the experience of players who have played the other games before.

Beyond the role of fatherhood, the Kaito Files also contrasts with the mainline Yakuza games in having a happy rather than bittersweet ending. The series is not known for happy endings. Yakuza 6 ends with Kiryu faking his death in order to allow Haruka to live a normal life outside of his shadow, and one of the final scenes of the game involve Kiryu writing a letter to the head of his weakening yakuza clan, run by a young man who Kiryu met as a child in Yakuza 0. The man’s father died early in the series, and Kiryu, in retrospect, realizes he distanced himself from him as a young boy when he should have served as a mentor and father figure. At the end of the mainline series, Kiryu feels forced to remove himself from the lives of his loved ones in order for them to be happy.

The Kaito Files is far more hopeful. At the end of the expansion, Kaito finds the woman he used to love, and he gets the chance to reconcile with her, able to close the loop and apologize for the immature person he was that made it impossible for their relationship to work out. For her part, his ex has also grown through struggle and better understands why Kaito felt pulled between his yakuza “family” and the one he had with her. Perhaps because Kaito is a side character, his story is allowed to end on a hopeful note, with the promise that perhaps this series allows some characters to live happy, normal lives.

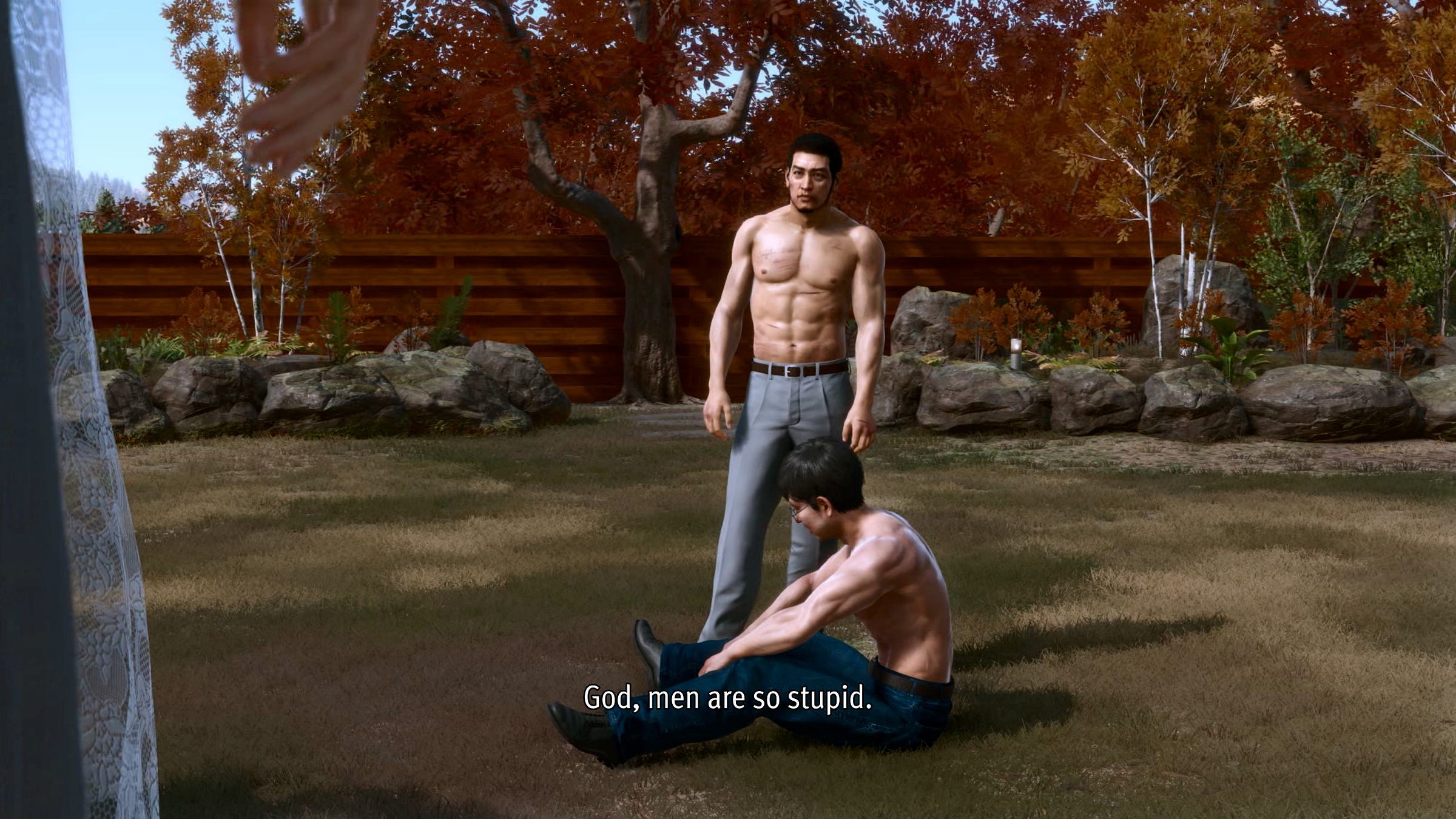

But all of this is just built up to the fact that the Kaito Files, and therefore Lost Judgment as a whole, ends with the best fight the series has ever seen, bar none. After Kaito defeats the main antagonist of his expansion, he goes back to the countryside to the home of a doctor who took care of his old girlfriend while she had amnesia. And for reasons that I will not spoil here, the two of them have a knock-out shirtless fist fight on the doctor’s front lawn. Neither of them hate each other; they respect each other greatly. But each of them feels driven by honor to beat each other up to prove which one of them is stronger as a man. It is over-the-top in the best way, and because credits roll shortly after the fight, you will leave the expansion and Lost Judgment as a whole with a smile on your face and an appreciation for how intentionally ridiculous the series can be. As long as future games retain this spirit, I will continue to play them.